Primephonic: The Early Life of a Pianist - An Interview with Haochen Zhang Part 2

Haochen talks to Primephonic about growing up in China, the contrast in approach between the Chinese and American music conservatoires, and his strongest influences.

After his Carnegie Hall performance, where pianist Haochen Zhang stepped in for Lang Lang who had withdrawn for health reasons, Haochen and I met at Knave to talk about his career as a pianist, inspirations in music, and his debut studio recording featuring works by Schumann, Liszt, Janácek and Brahms.

Primephonic

Jennifer Harrington

Haochen talks to Primephonic about growing up in China, the contrast in approach between the Chinese and American music conservatoires, and his strongest influences.

After his Carnegie Hall performance, where pianist Haochen Zhang stepped in for Lang Lang who had withdrawn for health reasons, Haochen and I met at Knave to talk about his career as a pianist, inspirations in music, and his debut studio recording featuring works by Schumann, Liszt, Janácek and Brahms.

How did you begin to play piano?

Where I grew up, my mom was one of the few people who listened to classical music and played it basically for me in her womb, this kind of “pre-birth education.” She never had an idea of introducing me to an instrument until she was taking English classes and as a part of her homework she had to read the American magazine, Reader’s Digest, every week. One week, when I was 4, there was one article that said piano was one of the best ways to raise a baby’s intelligence, and that really caught her imagination. It talked about how piano trains both your hands equally and both sides of your fingers move in the same kind of frequency.

Back in China then we were under the one-child policy. Intelligence was very important – it’s the future of your family. Since we were playing classical music all the time she thought ‘why not let him study piano’. I was always running around by myself so my mom thought it could be a way of communicating with an abstract thing and maybe piano can do that. So that’s how I started.

What was it like growing up in Shanghai? Are the music education and musical career expectations much different there than in the USA?

I was 14 when I auditioned for the Curtis Institute and moved [to the U.S.] when I was 15. In China it’s more systematic – the teachers I studied with are wonderful teachers but they are into details. They give you a very specific direction: what is right and not right. This Chinese way gives me a certain work ethic and discipline which is absolutely crucial because you need to be self-critical. It’s often mentioned in music you need two ears; one ear is enjoying the other is criticizing. Otherwise you can’t improve. In the States it’s an opening-up process. I still criticize myself in my own way but not in the teachers’ expectation. I am fortunate to have benefited from both.

Who inspired you from your time studying at the Curtis Institute?

My teacher Gary Graffman is a world-renowned pianist. He became a pedagogue and the director of Curtis. I’ve always looked up to him. The way he taught me and other students was very unique in that he didn’t force his own opinions on his students. There’s always this systematic approach in every successful teacher. How to make sound, technique, style and somehow Mr. Graffman avoided doing that. If you see other teachers and their students, you find that you can guess whose student it is. All students of the same teacher somehow have the same system, the way they produce sound or techniques or phrase, but in Mr. Graffman’s case, all his students are vastly different. This way really allows students to open themselves up and dig into their own personalities rather than copying the teacher or emulating them. The way I was able to develop a sense of self-awareness – who am I as an artist – I think that is very fortunate.

Are there artists that you look up to?

My favorite living pianists are Radu Lupu, who also won the Van Cliburn award, and Murray Perahia. Among the dead pianists would be Rachmaninov and the French pianist Alfred Cortot. They were part of the recording era when it started to become popular in the market. They played in a much different way that is lost in this generation, but I find something precious in that era that is very romantic and almost indulgent but not cliché.

Do you have any memorable performances?

I vividly remember playing with the Munich Philharmonic, one of my favorite orchestras, and I played with them Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4, a cornerstone piece of the late classical, early romantic eras. Munich Philharmonic is one of the most authentic German orchestras, and playing Beethoven’s 4th concerto is a really memorable experience for me. The conductor was Lorin Maazel. I played with him shortly before he died. His easy technique was so precise and the sound of the orchestra was so unique, so round, and so full. They played in a way that is seldom found in this authenticity.

Oh, and with the London Symphony Orchestra, playing the same Yellow River Piano Concerto one of the few times they performed it. British orchestras are playing so many concerts with not much time to prepare and are working like crazy. The end result was really beyond my expectations. The dedication they put into the performance was really inspiring.

Can you describe that difference, playing the Yellow River Concerto with the LSO and then NCPA?

Being a Western orchestra, you view the piece as you first learn it, which offers me an objective vision if we sort of block the original cultural heritage in China. With Chinese orchestras they know the piece inside out. Many of the older players lived through that period so there is a lot of feeling to it and of course, in terms of authenticity, playing with a Chinese orchestra provides that. However a foreign orchestra offers a fresh perspective.

Is there anyone who you hope to play with in the future?

In the future, I think it’s everyone’s dream to play with the Berlin Philharmonic. But there are also many amazing orchestras I look forward to playing with.

So, I’m sure you’ve got a full and exciting schedule ahead. What performance projects do you have in the upcoming year?

I’m certainly looking forward to the New York recital debut in Zankel at Carnegie Hall. I’ve never played my recital in New York City. It’s the arts center of America. I’ve always wanted to come here and play and it’s really exciting for me that I can play my recital here for the first time.

Image credit: Benjamin Ealovega

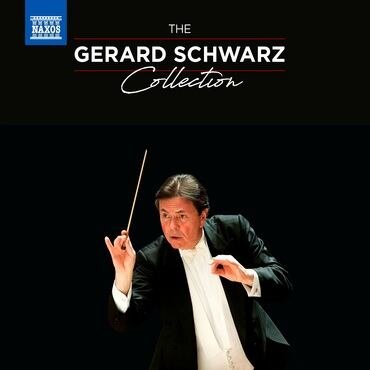

Primephonic: Gerard Schwarz at 70 - An Interview

Gerard Schwarz, music director of the All-Star Orchestra and the Eastern Music Festival, and Conductor Laureate of the Seattle Symphony, enters his 70th year. Marking the occasion, an impressive 30-disc album has recently been released on Naxos Records. Primephonic caught up with him to discuss his impressive career, superb recordings and unstoppable endeavours.

Primephonic

Gerard Schwarz, music director of the All-Star Orchestra and the Eastern Music Festival, and Conductor Laureate of the Seattle Symphony, enters his 70th year. Marking the occasion, an impressive 30-disc album has recently been released on Naxos Records. Primephonic caught up with him to discuss his impressive career, superb recordings and unstoppable endeavours.

The Gerard Schwarz Collection has been released to mark your 70th birthday, showcasing retrospective recordings in a 30-disc album. This year also saw your memoir published and Emmy Awards. What are your thoughts on what has been a year of exciting events?

It’s a dream come true to have all of these things come together at the same time. The memoir I wrote of course was very meaningful to me. I never was intending to write one but for a variety of reasons, there it was. It’s called Behind the Baton. It’s about performances, it’s about repertoire, it's about conducting, but it's also about living a life in music. There are many lessons to be learned as you go along and I thought for future generations I might be able to give them some hints on how I dealt with issues that came about like building a hall and building an orchestra.

And with the recordings, Naxos had approached me with this idea and I contacted Nonesuch where I had done about 21 or so LPs. Many of these were never released on CD, and many which were released on CD were out of print. I even had to transfer some LPs, which was really interesting, and once Nonesuch said yes, the process began. With the great support of Klaus Heymann, I thought “Wow, we really have something here.”

We found a version of Schubert’s Third recorded with the New York Chamber Symphony that was never edited and we had a Schubert Ninth that I really wanted to get out but the tapes had disintegrated, and then it went from there! There are some Handel Arias which I really love and I wanted Mozart to be part of it. We did the Brahms Schoenberg Piano Quartet from the Eastern Music Festival, and of course many of my old trumpet recordings. I thought it was important that I included a few CDs of American repertoire that has been so important in my life. It was a thrill. And 30 CDs is a lot of CDs!

Photo credit: Steve J. Sherman

I also recently did a program with the Juilliard Orchestra that was like a dream come true for me. Difficult music of Diamond, Druckman and Schulman. All composers associated with the school. I was just thrilled and the kids loved it. All this stuff is going on this year and it makes me extremely happy.

You were music director with the Seattle Symphony for 26 seasons and are now conductor laureate. It must be an honour to have led one of the world’s top orchestras. What was your biggest achievement during your time there?

Starting from where it was artistically and bringing it to a new level and broadening the repertoire was so important to me. And then, of course, helping to build Benaroya Hall. I believe there are five things you need for success. The first are talent and intelligence. The second is work ethic, you have to work very hard. Then a positive attitude, I call it a yes attitude. And there’s willingness to do anything, to go beyond the job description. I thought about that a lot, it’s not just something that I’ve come to casually and I see it all the time, in my kids and in my own family. And it’s also not just in music, it can be in any career.

You are known for championing works by American composers, such as Walter Piston, William Schuman, David Diamond and Philip Glass. What was in your opinion, the most significant performance you conducted?

What jumps out at me are a few things. Doing all the symphonies of Schuman for Naxos Records was extremely significant, it had never been done before. There’s a recording here or there of this piece or that piece, but we’ve never had them all, so that was very important. To do a live recording of the Deems Taylor opera Peter Ibbetson and get a live recording was very important as well as Howard Hanson’s Merry Mount was also a big opera. To do David Diamond’s 10th Symphony, which I think was a significant event for me and the orchestra. It was the only symphony premiere I did of his. The others were premiered by Mitropoulos, Koussevitzky, Munch, Ormandy, Bernstein and Masur, so it was nice to be part of that group.

The Emmy-Winning All-Star Orchestra TV Series was filmed with an impressive 18 high-definition cameras and is back for a new season. The orchestra is made up of players from some of the country’s top orchestra. Did you hand-pick the players?

In my last years in Seattle we did a few television shows where the format was not live. We would record two to three performances and do some packages around them with educational talks and interviews. They were quite successful. Then we were actually allowed to record one without an audience, so we had performances on Thursday, Saturday, and Sunday, but none of Friday. I asked Andre Watts and the orchestra if they would consider doing a performance on Friday morning with nobody in the audience so we could get better camera shots. They all agreed, we did it, and it was incredible. That show won Emmys and I thought to myself, what an interesting idea.

“Made for television” concerts really hadn’t existed in this country since the late fifties. Everything was “Live” and always two hours with intermission and filler so I thought to myself what if we went back and did an hour-long concert with a talk surrounding it. And then from all the material we have now recorded, do some really significant educational work. That’s how it came about. I went to a group of friends in Seattle and told them I had this idea. Actually Jody my wife named it, and I said I wanted it to be fundamentally American, like all-star baseball. Then I got a half dozen people together who were friends and said “Hey, why don’t we try this”. That was the genesis of the very beginning of it.

Photo credit: Ben Van Houten

What would this orchestra be? Then I thought why not ask my friends at a variety of American orchestras to participate. I didn’t want it to be associated with just one orchestra, I wanted it to be associated with American orchestras. We have players from 30 different orchestras.

And then there’s how. Well I chose my friends, I got recommendations as necessary from them and then each section was happy. I tried to get many leaders from major orchestras. That’s how it all began.

What was your reason for starting up the All-Star Orchestra?

We produced the TV shows thus far and we have won six Emmys, but I really wanted to get an important educational component. So the first year we did a lot of interviews with experts and players, not knowing what we were going to do with it, but I wanted to somehow make a difference educationally. I feel the two big issues are exposure and education. So the exposure part was covered, television was free and I wanted education part to be free as well. I wanted to give music teachers more tools to enhance what they were doing. With all this material, we were able to convince the Kahn Academy to do some music education, which they had not done before. We raise money for everything and it becomes available for free. So far we’ve reached 6 million students.

My hope is that 6 years from now, someone goes to the Philadelphia Orchestra and says “Oh, I first saw David Kim with the All Stars and fell in love with his music and his violin and now I really want to come to Philadelphia Orchestra concerts.”

Do you have any advice for young budding conductors?

There’s a lot of advice and a lot of it is in my book but you have to study really hard, you have to really know music. So many kids study beat and time and that’s of minimal importance. What’s important is knowing musical ideas and making performances. Having all the qualities that I spoke about before in terms of success. To take advantage of every opportunity. If they ask, “Would you conduct the local band?” say yes. Do everything you can do and most importantly have perseverance. It rarely comes easily or quickly, you have to stick with it. I don't know any conductors that haven’t had to continue to persevere at it. Many give up but you need to have the energy to keep going.

What do you see for the future?

Conducting all over the world, which I love. My number one priority is the All-Stars and music education, helping its resurgence in the schools. I want us all to be flourishing in this world. My main focus is to think about that. I’m composing a lot. I enjoy it, which is shocking to me because I never used to.

I’ve done now three TV shows with the Marine Band in the same format as All Star Orchestra to teach about band music because music lovers at orchestra concerts don’t know what a band is or the repertoire is. And, hopefully we’ll be doing more shows with the All-Star Orchestra.

Gerard Schwarz in conversation with Jennifer Harrington

Primephonic: Owning the Music - An Interview with Haochen Zhang Part I

The morning after his Carnegie Hall performance, where pianist Haochen Zhang stepped in for Lang Lang who had withdrawn for health reasons, Haochen and I met at Knave to talk about his career as a pianist, inspirations in music, and his debut studio recording featuring works by Schumann, Liszt, Janácek and Brahms.

Primephonic

Jennifer Harrington

The morning after his Carnegie Hall performance, where pianist Haochen Zhang stepped in for Lang Lang who had withdrawn for health reasons, Haochen and I met at Knave to talk about his career as a pianist, inspirations in music, and his debut studio recording featuring works by Schumann, Liszt, Janácek and Brahms.

You just performed at Carnegie Hall filling in for Lang Lang. How was the performance?

I played the Yellow River Piano Concerto with the China NCPA Orchestra. The concerto is a cornerstone of Chinese music. It was a refreshing night; the concerto is new in the West so it feels different to perform it in front of this audience. In China, eating Chinese food feels like air, where you are not aware of its existence, but in America it’s like eating your first ever Chinese meal, where you’re acutely aware of the experience and feeling how the audience responds makes any performance exciting.

This has been a fruitful year for you, having won the Avery Fisher Career Grant and your solo album (on BIS) was released this year. Tell me a bit about this positive string of events.

The Avery Fisher is a very encouraging thing for me. It’s a prestige award. Unlike other awards where they give you engagements or performances, it’s the prize by itself (and some cash), and it’s only given to young musicians. Studying at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, a lot of faculty members and renowned musicians started their careers winning the Avery Fisher award. I’m honored to be in this line of heritage and continuity. In a way it gives me more responsibility, knowing that the previous recipients are musicians such as Gil Shaham and Hilary Hahn.

You have won several really impressive competitions, such as the Thirteenth Van Cliburn Piano Competition back in 2009. This must have been a career-changing experience: following this you were propelled onto the world’s most prestigious concert stages. How has your career developed since that time?

I hope I’ve matured, since it was 8 years ago. I’ve been performing a lot of concerts which is a way of maturing yourself. It’s different from practicing yourself. A concert is a different way of learning. And with traveling the world you see different kinds of audiences, where you find cultural differences and most importantly, the solitude you have to overcome on the road by yourself, meeting new people every day. You’re not in a settled community so you have to overcome this to mature yourself. I feel I’ve overcome this. Not only has travel become part of a part of my job, it’s no longer my job. It’s the journey of a musician.

Going back to your album of solo piano works by Schumann, Liszt, Janácek and Brahms, released in February: what inspired you to record this particular repertoire? What was the highlight of creating this album?

At BIS (record label) it’s more about what artistic statement you can make, and in terms of audio quality, most labels choose the standard but BIS is particular because they keep the highest quality by using SACD (Super Audio CD), and they believe in good quality of sound. They also let me choose whatever repertoire I want to play, so I really appreciate BIS.

What do you feel your artistic statement was?

With Schumann, Liszt, Janácek and Brahms, they’re all introspective in different ways. They share this reflective quality which I thought is really precious. Young pianists in my generation are more inclined to play (and the audience is more familiar with hearing) virtuosic pieces. I want to show another side of a young pianist. It feels natural to me. I’ve always been a somewhat introverted person. Growing up in China, which is a culture of inward-looking perspectives, I have this personality and was always drawn to music that has an introspective and reflective quality. You feel like your soul is being cleaned. I wanted to make my first studio recording about who I am and what statement I want to make as an artist.

What repertoire do you hope to explore in your recordings and performances?

I’ve always been a curious person, so I’m looking to explore all kinds of different styles. It interests me more when there are pieces that have an insight into something deeper or are inward-looking, with incredible emotional and intellectual depth. I’m certainly interested in digging into Beethoven, Schumann, and Schubert; and I’m always a Brahms fan and hope to record more late Brahms.

Is there a piece you love to play or that you feel you ‘own’?

That always changes and that’s the beautiful thing about music. There are pieces that you didn’t like two years ago but now you’re falling in love with. There are pieces you regard as something holy or untouchable but now they are more tangible and you’ve pulled the piece from that status to somewhere where you can look at it. And there are pieces you always like and they stay the same for 20 years. In terms of composers, I never found myself having one favorite composer but it always switches through those four.

In terms of owning a piece, the more you play it, the more you feel like you own it. The process of owning it goes with the amount of performances. It’s the physical and spiritual combining together. You feel like your fingers are literally your spirit – what I think, and what I execute, and how people respond to it. That one moment you feel like you are the music and the music is you. That is the most rewarding feeling as a musician.