Chicago Tribune: Shanghai Symphony Brings 140-Year Tradition to America

When the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra makes its Chicago-area debut Aug. 16 at the Ravinia Festival, no one will be prouder of the occasion than its music director, Long Yu.

Chicago Tribune

Howard Reich

When the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra makes its Chicago-area debut Aug. 16 at the Ravinia Festival, no one will be prouder of the occasion than its music director, Long Yu.

For to him, the Shanghai ensemble will be more than just a visitor from the other side of the world – it will be bringing with it a legacy stretching back to 1879, when it was established under a previous name.

“This is the first orchestra not only in China, but in the Far East,” says Yu, speaking by phone from Hong Kong.

“A lot of work was premiered in Asia by the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra. For example, Beethoven’s Ninth (Symphony), (Stravinsky’s) ‘Firebird’ – all those pieces premiered in Shanghai.”

In effect, adds Yu, this orchestra “introduced most of the classical music to China and to Asia.”

That in itself is significant, but all the more considering the dramatic growth of classical music in China and elsewhere in Asia. We may lament the shrinking and aging of the classical audience in the United States, with only the most celebrated soloists and ensembles able to fill large concert halls and festivals that routinely sold out in the mid-20th century. But in China and environs, the music seems to be on a perpetual rise.

Read more here.

Finnish Music Quarterly: Grappling with Sibelius in China

“Could a certain distance from Western symphonic thought have contributed to the surprising qualities of the performances I heard in China?” Andrew Mellor reviews performances of Sibelius’s Symphonies Nos 2 and 5 in Shanghai and Guangzhou.

Finnish Music Quarterly

Andrew Mellor

“Could a certain distance from Western symphonic thought have contributed to the surprising qualities of the performances I heard in China?” Andrew Mellor reviews performances of Sibelius’s Symphonies Nos 2 and 5 in Shanghai and Guangzhou.

The Shanghai Symphony Orchestra – 140 years old this season – presented Sibelius’s Symphony No. 2 at a concert on 13 January conducted by Li Xincao. Sibelius is not a regular part of the SSO’s diet, I was told by Doug He, the orchestra’s Vice President. Sometimes the Violin Concerto crops up in a season. There might even be, as in this season, a symphony included. But there was zero Sibelius in the season before. Like the Orchestre de Paris, however, this is a flexible modern symphony orchestra with strength in all sections and high levels of discipline.

Li Xincao and the SSO’s Sibelius was exceptional, perhaps because it grasped some of the basic principles mentioned above. It appeared to take rhythm as a starting point, understanding that a focus on the rhythmic devices presented from the very start of the score will allow those devices to take on the kinetic significance they need. Intentionally or otherwise, the orchestra spoke relatively plainly but still with a sure sense of colour (the solo trumpet playing was deliciously peaty). The performance acknowledged the strain in the music, as in the final movement when building disquiet metamorphoses into natural release.

Read more here.

Forbes: Isaac Stern's Pioneering Spirit Lives On Via Shanghai Event, $100,000 Prize

Though [Isaac Stern] died at age 81 in 2001, his spirit lives on in the Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition, a bi-annual international violin competition to be held starting Aug. 10 with winners to be announced on Sept. 1. The $100,000 first prize is the largest in the world for a violin competition.

Forbes

Russell Flannery

American violinist Isaac Stern found friends and fans in China when he made pioneering visits to the country in its early reform days in the 1970s and 1980s. Though he died at age 81 in 2001, his spirit lives on in the Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition, a bi-annual international violin competition to be held starting Aug. 10 with winners to be announced on Sept. 1. The $100,000 first prize is the largest in the world for a violin competition.

The event, which is being organized by the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, will be held against a backdrop of growing interest in classical music in China, according to Long Yu, the event president and a top China maestro.

Read more here.

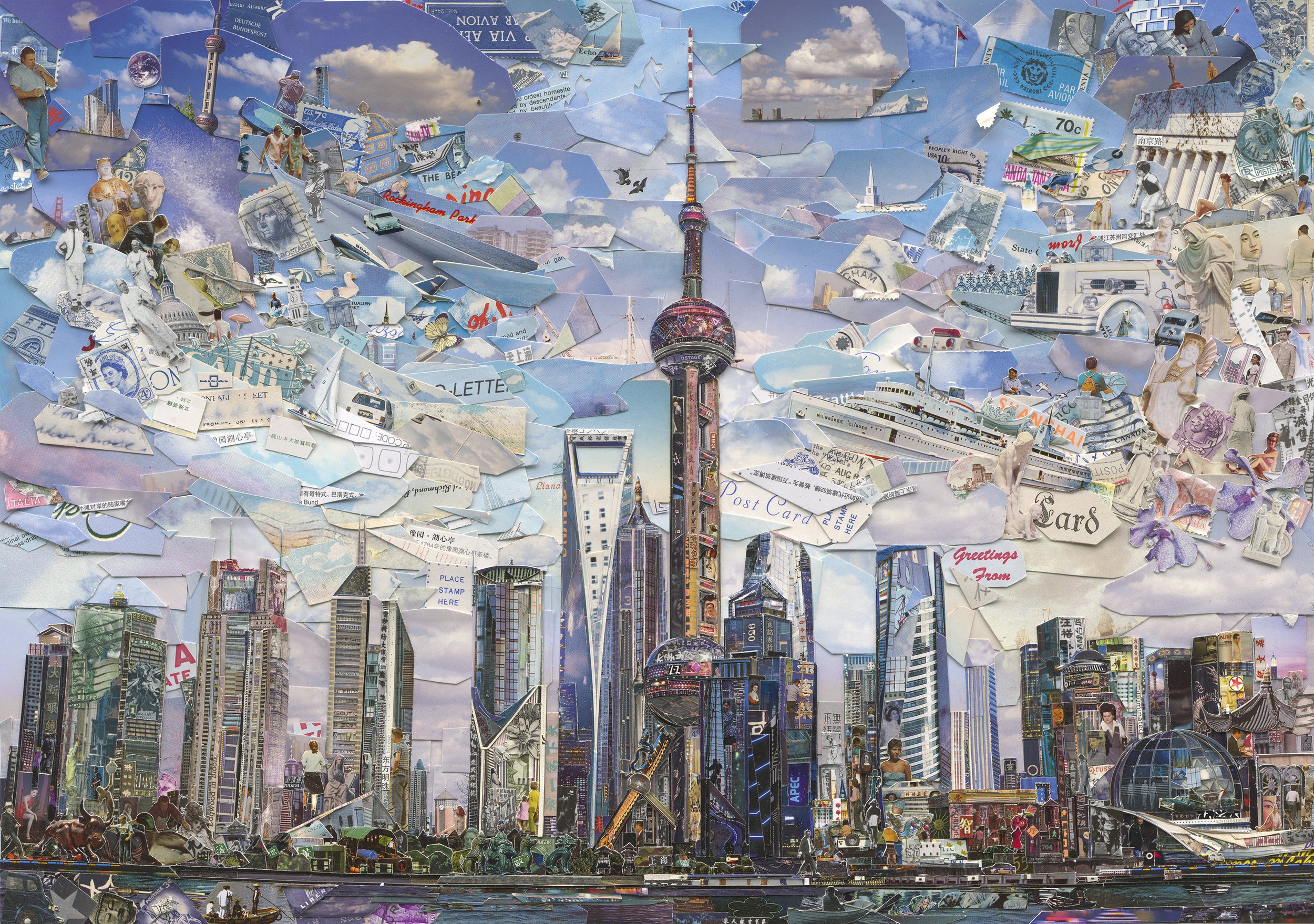

The Strad: Postcard from Shanghai - Competing with the Traditional

The SISIVC is one of a number of music competitions to have sprung up in Asia over the past few years; with a $100,000 first prize, its inaugural edition this August [2016] attracted high-level performers from 26 different countries.

The Strad

December 2016 issue

By Pauline Harding

"All around me, bamboo-like slates rise up to a ceiling made from giant, woven strands of what looks like flax; horizontal strips of wood demarcate different floors. I could be sitting in a giant dim sum basket - but in fact it is Shanghai's Symphony Chamber Hall, where I am awaiting the first contestant in the final section of the Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition (SISIVC) semi-final. And indeed, things are about to heat up, as 18 contestants prepare to perform Mozart's Third Violin Concerto, all with their own cadenzas...."

Purchase The Strad for the full article, here.

The New York Times: Shanghai Violin Competition Celebrates Isaac Stern’s Legacy in China

The inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition concluded on Friday after nearly three weeks of intensive performances by 24 young violinists from around the world. Mayu Kishima of Japan was awarded first place, taking home the grand prize of $100,000, the largest single award for an international violin competition.

The Japanese violinist Mayu Kishima was awarded the first prize at the inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition on Friday. Credit: Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition

The New York Times

By Amy Qin

More than 35 years after the violinist Isaac Stern made a groundbreaking visit to China, his legacy there lives on.

The inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition concluded on Friday after nearly three weeks of intensive performances by 24 young violinists from around the world. Mayu Kishima of Japan was awarded first place, taking home the grand prize of $100,000, the largest single award for an international violin competition.

“We were looking for the kind of spark and commitment to music that our father would have embraced,” David Stern, co-chairman of the jury committee, said in a telephone interview from Shanghai.

That Isaac Stern, who died in 2001, now has a competition bearing his name is somewhat ironic given his aversion to such events.

So when the conductor Yu Long, a towering figure in classical music in China, raised the idea of holding a competition about two and a half years ago, “it was not the easiest idea for the three of us to approach,” Mr. Stern said, referring to his brother, Michael, and his sister, Shira. “Our father did everything he could to mentor young musicians in order to avoid competitions.”

Isaac Stern’s dedication to training young musicians was perhaps most vividly captured in the 1979 documentary “From Mao to Mozart: Isaac Stern in China.” The film, which won an Academy Award for best documentary feature, chronicled Mr. Stern’s two-week trip to China for a series of concerts and master classes.

That visit, which came just as China was emerging from decades of self-imposed isolation and political tumult, is credited with having influenced a generation of young Chinese musicians, including Mr. Yu, who recalled sitting in the audience as a teenager during one of Mr. Stern’s performances in Shanghai.

“During the Cultural Revolution, we didn’t have many opportunities to play Western music,” Mr. Yu, now conductor of a number of ensembles including the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, said in a telephone interview. “Then, in that moment in 1979 when Maestro Stern came, we suddenly felt the difference in how we could understand music.”

Since 1979, classical music in China has grown tremendously, with gleaming concert halls being built around the country and some 40 million young Chinese studying the violin or the piano.

Still, Mr. Yu said, “The problem in China, and Asia more broadly, is that the players are more concerned about technical issues.”

So when it came to this new project, both the Stern family and Mr. Yu agreed that they wanted to make a more comprehensive competition that would reward musicians not just for technical ability, but also for all-around dedication to music.

After two years of discussions and planning, the Stern family and the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra came up with a competition structure that David Stern said his father, even with his distaste for competitions, probably would have approved. This meant including elements that were important to Isaac Stern, like chamber music and Chinese music.

For example, contestants in the semifinal round were required to perform two concertos: “The Butterfly Lovers,” a popular Chinese concerto composed in 1959 by He Zhanhao and Chen Gang, and Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 3 with a chamber orchestra (with original improvisation during the cadenza section). They also had to play a violin sonata, as well as the first movement of piano trio by Schubert or Brahms.

The 24 contestants represented several countries, including China, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea and the United States. In addition to the prize money, Ms. Kishima will also receive performance contracts with several international symphony orchestras.

Sergei Dogadin of Russia was awarded the second prize of $50,000, and Sirena Huang of the United States took home the third prize of $25,000. The violinists Zakhar Bron of Russia and Boris Kuschnir of Austria were among the 13 who sat on the jury.

The competition also presented an Isaac Stern Human Spirit Award of $10,000 each to two noncontestants: One, to Wu Taoxiang and Du Zhengquan, who founded the Einstein Orchestra, a middle-school ensemble in China, and the other to Negin Khpalwak, who directs an orchestra for women in Afghanistan, for “their outstanding contribution to our understanding of humanity through the medium of music.”

Most of the funding for the competition, which will be held every two years, came from corporate sponsors, according to Fedina Zhou, president of the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra. The symphony has been expanding in recent years, forging a long-term partnership with the New York Philharmonic and, in 2014, unveiling a new hall where the competition was held.

For many musicians and music lovers in China, the competition represents further validation that China is well on its way to becoming a heavyweight player in the classical music world.

“At last the Chinese people finally have an internationally recognized competition of their own,” said Rudolph Tang, a writer and expert in Shanghai on the classical music industry in China. “It has everything that a top competition should have, like a top jury, great organization, and high prize money.”

“It is like a dream come true,” he added.

Strings Magazine: Shanghai Symphony Orchestra Announces Isaac Stern Violin Competition

In September, the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra announced the launch of the large-scale competition, which will offer $100,000 to the first-prize winner, making it the single largest monetary award for a violin competition.

Strings Magazine

By Stephanie Powell

"It has taken a little bit of time," David Stern, son of violinist Isaac Stern, modestly says of launching the Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition (SISIVC) that he will be co-chairing. In September, the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra announced the launch of the large-scale competition, which will offer $100,000 to the first-prize winner, making it the single largest monetary award for a violin competition. "I have to say that my father, in his lifetime, was not a great proponent of competitions," Stern says over the phone from Paris. "He didn’t believe in competitions very much and he didn’t believe in the concept of competing in music."

This was a belief that, when Long Yu (artistic director and chief conductor of the China Philharmonic Orchestra and music director of the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra) approached David and his brother Michael with the idea of developing a competition to honor their father’s legacy and commemorate his relationship with China, left the pair of brothers in a quandary. "There’s the whole feeling that we are responsible for his legacy," David says, "and we want to do it as carefully as possible."

The brothers knew that China was a significant part of their father’s life. From Mao to Mozart, the Oscar-winning documentary highlighting Stern’s 1979 travels to China shortly after the end of the Cultural Revolution marked the beginning of a long love affair with the country and its musical community. In many ways, the trip served as the initial bridge between Western and Eastern music.

With their father’s ethos in mind—"thinking ahead, being on top of things, and not just doing what everyone else does"—the brothers decided to move forward with the competition. They were helped by an all-star cast, including advisor to the festival Yo-Yo Ma, whom David mentions during our call, "It’s his birthday today! I have to call him."

"We thought about today’s society and how difficult it is for young musicians to get themselves heard," David says, "and we thought if we could infuse this competition with aspects that reflected my father’s legacy and his principals, then it would not just be another competition.

"There will be a round where [finalists] will have to perform with a pianist and cellist and perform in a trio. That just tells you so much about the musician that a concerto doesn’t necessarily. Chamber music was so important to my father’s being." The competition will also include a Mozart round, where finalists will have to improvise their own cadenzas.

"As long as we maintain as much as possible that it’s not your ordinary competition," David says, "then we will be doing service to him. I feel like I’ve been connecting to him on a daily basis. Yu Long and the Chinese musical community have shown such understanding and respect for what my father stood for, and they speak about him in such a wonderful way," David adds, "I feel like we’re doing the right thing."

The application period is open now, for international violinists ranging in ages from 18 to 32, through January 31, 2016, and the competition is scheduled to run from August 14 through September 2, 2016, in Shanghai. A prize of $50,000 will be awarded for second place, and $25,000 for third with two additional awards available for the best performance of a Chinese work and the Isaac Stern Humanitarian Award.

For more information on the competition, visit shcompetition.com.

SSO to Mark Anniversaries in Performance at the UN General Assembly

For the UN concert on August 28, artists from all the major Allied powers of WW2 will be represented, performing music by Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, John Williams and a new work by Zou Ye

In one of the largest concerts ever held at the General Assembly of the United Nations, August 28 will see Maestro Long Yu assemble his Shanghai Symphony Orchestra to represent China in a musical celebration to mark 70 years since both the ending of World War Two and the establishment of the UN itself. All of the chief Allied WW2 powers will be represented in the concert, which also will include America's MasterVoices choir (formerly the Collegiate Chorale, the choir which performed at the official opening of the UN building), Russian-born violinist Maxim Vengerov (playing Schindler's List), 12-year-old Chinese piano prodigy Sirena Wang, and singers Ying Huang (China), Sarah Fox (UK), Aurhelia Varak (France), Vadim Gan (Russia), David Blalock (USA) and Christopher Magiera (USA). The concert is part of a tour of the Americas by the orchestra, and will also take in two venues in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Aug 30, 31), and one in Buenos Aires, Argentina (Sept 2).

"It is a concert in which the music we play is about memories and about new beginnings" says Long Yu, "World War Two was of course a great tragedy, as well as a victory over evil, which must be remembered, while the birth of the UN from out of the wreckage of that war was a new beginning for the world. So Tchaikovsky's Andante Cantabile is contemplative, healing, Barber's Adagio is a piece of hushed mourning, as of course is John Williams's Theme from Schindler's List. Then Beethoven's Choral Fantasy is a work of genesis, one that eventually culminated in the magnificent Ninth Symphony and its 'Ode To Joy' - but in this exuberant early work we can hear the seeds of that utopian vision, which is very appropriate for a forum created around the ideal of nations talking and collaborating, rather than fighting." The new work, Shanghai 1937, is by the Chinese composer Zou Ye (Long Yu recently initiated the Compose 20:20 project, to bring new Western works to China, and new Chinese works to the West).

Nor does the sense of history that attends this event elude its conductor. "Speaking for myself and the players as well as the management of the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, to be able to represent our country in the spirit of the great things achieved by the allies and the founders of the United Nations seven decades ago, is an immense privilege. To be part of a cultural message from artists of China, the US, UK, France and Russia that we hope represents the renewal of those ideals is an honor to be cherished. And it also feels appropriate that this concert is part of our wider tour of the Americas - as much as we are bringing in artists from different nationalities to our concert halls, we musicians are also ourselves physically travelling from country to country, to help strengthen the bonds that bind nations, and people, together."

The orchestra will also be joined by nine students from the Shanghai Orchestra Academy, an initiative created with international cooperation with the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

Notes for Editors:

* The Shanghai Symphony Orchestra is China's oldest symphony orchestra, founded in 1879 as the Shanghai Public Band (under conductor and flautist Jean Remusat). Between these years and the end of World War Two, some European musicians came to the orchestra as section leaders, bringing with them their knowledge of European performance styles - after World War Two, however, the Europeans gradually left creating opportunities for the most talented Chinese musicians. In 1956 the orchestra, already informally known as "the best in the Far East", renamed itself the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra. Xieyang Chen took over the artistic leadership, creating and filling the role of music director. He was succeeded by the current incumbent, Long Yu.

The SSO has performed around the world. It was the first Chinese orchestra to play Carnegie Hall, in 1990, the first to play the Berlin Philharmonie (2004), the first to give a concert in New York's Central Park (2010). Last year, it inaugurated its new, world-class concert venue in Shanghai, Symphony Hall, ingeniously built underground for urban planning reasons. And it also recently created a major new popular classical music festival - MISA (Music in the Summer Air) - with joint artistic directors Long Yu and Charles Dutoit.

In 2014 the SSO and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra launched the NYPO's Shanghai Orchestra Academy and Residency Partnership, a joint endeavour of both orchestras that included the founding of the Shanghai Orchestra Academy (SOA) which opened in September 2014, and the NYPO's four-year performance residency in Shanghai.

* Maestro Long Yu is Music Director of the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, also of the Guanzhou Symphony Orchestra, the Artistic Director and co-founder of the China Philharmonic Orchestra, and Principal Guest Conductor of the Hong Kong Philharmonic. He is also Founding Artistic Director of the Beijing Music Festival, co-founder of the Shanghai MISA Festival and incoming Principal Guest Conductor of the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra.

He helped spearhead the establishment of the New York Philharmonic's Shanghai Orchestra Academy and Residency Partnership (see above) and is an honorary member of the International Advisory Board of the New York Philharmonic. Other China ‘firsts’ include bringing the first-ever performances of Wagner’s Ring cycle in the country, presenting its first-ever Mahler cycle, releasing the first album of Chinese music on a major recording label (Dragon Songs, alongside Lang Lang, for DG), and bringing the first-ever Chinese orchestra to play at the Vatican. Last year, he led the China Philharmonic as the first Chinese orchestra ever invited to play at the BBC Proms. The Shanghai Symphony under his baton was the first orchestra other than the New York Philharmonic to perform on Central Park's Great Lawn.

He has commissioned new works from many of today’s leading composers, among them Tan Dun, Krzysztof Penderecki, Philip Glass, John Corigliano, Guo Wenjing and Ye Xiaogang and has created a five-year initiative, Compose 20:20, to bring new Chinese works to the West and new Western works to China.

He was recently awarded the Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur from the French governnment, only the third Chinese national ever to receive it. This award marked a highlight of an impressive 2014 season for Maestro Long Yu. Last July, starry concerts in Shanghai and Beijing coincided with his 50th birthday, and colleagues including Lang Lang, Alison Balsom and Maxim Vengerov performed, with new works composed by Tan Dun, Qigang Chen and John Williams. At the same time, he led the Shanghai Symphony into their new home, a state-of-the-art venue built mostly underground, acoustically designed by Yasuhisa Toyota.

Long Yu regularly conducts important orchestras and opera houses in the West such as the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Orchestre de Paris, Chicago Symphony, BBC Symphony, Teatro La Fenice, Hamburg Staatsoper and Philadelphia Orchestra. He was previously honored to be appointed a Chavelier dans L’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France, and a L’onorificenza di commendatore from the Republic of Italy.

In August 2015 he led the China Philharmonic on a tour of the old Silk Road trade route, taking in coutries such as Athens, Turkey and Iran - making China the first of the P5+1 negotiating partners to send an orchestra to Tehran following the much-discussed nuclear agreement (they played Dvorak's New World Symphony, among other repertoire).

Financial Times: Overtures that Bridge East and West

How one of China's top conductors, Long Yu, is extending the appeal of his country's music.

Financial Times

Photo: Yao Xu

Put together a pair of anniversaries as far-reaching as those falling this year — the end of the second world war and the founding of the UN in 1945 — and it is fitting that as many nationalities as possible are involved. On Friday the UN marks the double anniversary with a special invitation-only concert, with soloists from each of the major Allied powers, together with the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra and Chinese conductor Long Yu.

It is the start of a tour of the Americas by the orchestra, and will be repeated in Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires.

One element of the concert may be unexpected: the inclusion of a new work by a Chinese composer, Shanghai 1937 by Zou Ye, part of a project called “Compose 20:20” and a sign of how much the world of classical music has changed since 1945. Look to the future and it is likely to be found in Asia — thanks not only to the hordes of young pianists following in the footsteps of Chinese superstar Lang Lang, but also to new and interesting composers.

There is what Long Yu calls a “cultural bridge” between east and west waiting to be crossed. Any composer who wants to make the journey from the Chinese classical tradition to the concert halls of the west needs an uncommon degree of ingenuity, and nobody understands this better than China’s leading conductor. In recent years he has been successful in bringing a string of new Chinese works to the west (UK music-lovers will recall Qigang Chen’s Joie éternelle when the China Philharmonic made history as the first Chinese orchestra to visit the BBC Proms in 2014).

“Actually, it’s more than a hunger,” says Long Yu. “It is an absolute need, if we are to keep the cultural fires alive. We have seen so far a wonderful fascination in China for western classical music, and the same coming the other way from the west. But this frenzy of energy has too often been somewhat diffuse and without shape. Now is the time that we can start using it to explore and to experience in a curated way.”

That “curated way” is “Compose 20:20”. Between now and 2020, Long Yu will present 20 new works by Chinese composers in the west and 20 contemporary works by western composers in China. “Some of the composers are good friends, like Qigang Chen and [Polish composer Krzysztof] Penderecki,” says Long Yu. “Some, like Philip Glass, I have already commissioned; others not, such as John Adams and Bright Sheng. If ‘Compose 20:20’ can provide the motivation to generate commissions, I will count it a success.”

A nation coming out of the cultural revolution needed its own version of Britain’s inimitable Thomas Beecham, serial founder of orchestras and, in Long Yu, China has found him. Among the exhausting array of positions he holds are artistic director and co-founder of the China Philharmonic Orchestra, music director of the Shanghai and Guangzhou Symphony Orchestras, founder of the Beijing Music Festival and the Shanghai MISA Festival.

It might seem a challenge to introduce a programme of new Chinese music in the west, but Long Yu argues that audiences across the world are equally suspicious of what they do not know.

“In China, the taste in music varies hugely between different areas,” he says. “For example, people in Beijing love Wagner. Our Götterdämmerung there didn’t finish until one in the morning, but the audience stayed for many curtain calls. Contrast that with a concert we did of extracts from Wagner’s operas in the south, where there just wasn’t the same enthusiasm. For a long while China stuck with Tchaikovsky and endless repeats of La traviata and La bohème. But more recently there have been so many premieres — Stravinsky, Ligeti, Britten’s Peter Grimes and War Requiem, even Berg’s Lulu, as far back as 2002, and that was tough. Half the audience left the theatre at the end of the first act. You have to keep fighting to bring forward new works.”

This is part of the picture that Long Yu paints of a country that has moved on from laying the foundations for a new artistic life after the cultural revolution. The previous generation, he says, had to work out what the best system for the arts might be in China, what the professional structures would look like. The present generation, he says, has to build on that.

“I am very committed to moving on to the second-level cities in China and encouraging their development,” he says. “People are critical of China for building new concert halls and theatres, as the buildings are nothing more than symbolic unless there is content. Now we are working on the next part of that. Music is something you can’t see, can’t touch. It comes from creativity, and we have to show the younger generation that music is not just about giving a concert or having a career. It is about freeing the imagination.”

From his unique position of influence Long Yu is able to take the long view. “What matters to me now is that one generation passes on the fire to the next. We have this one-child policy in China and every parent wants his kid to become a star. People talk about 50m Chinese children learning the piano, but do we really think all 50m will find a job as a musician? There isn’t too much space for stars.

“I would be quite happy if those 50m grow up to become music-lovers, the people who buy tickets and support music in the future. That would make me happier than seeing the kids struggling to perfect their harmony every day. If only their parents could see that what is important is how to bring joy through music to their children.”