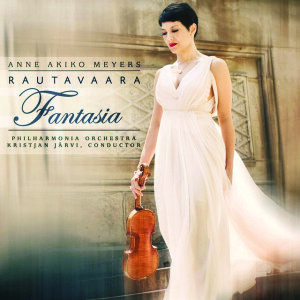

Strings: Violinist Anne Akiko Meyers on a First and Final Commission from Rautavaara

Anne Akiko Meyers called her new CD Fantasia after the transcendent 15-minute-long concerto that Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara wrote for her, which turned out to be the last [composition for violin] he composed before his death in July 2016 at the age of 87. Meyers will give the world premiere of Fantasia in March with the Kansas City Symphony conducted by Michael Stern; the recording was made in London with the Philharmonia conducted by Kristjan Järvi

Strings

By Laurence Vittes

Anne Akiko Meyers called her new CD Fantasia after the transcendent 15-minute-long concerto that Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara wrote for her, which turned out to be the last [composition for violin] he composed before his death in July 2016 at the age of 87. Meyers will give the world premiere of Fantasia in March with the Kansas City Symphony conducted by Michael Stern; the recording was made in London with the Philharmonia conducted by Kristjan Järvi.

Due out early in 2017, the new CD will also include Ravel’s Tzigane, Szymanowski’s Violin Concerto No. 1, and new orchestrations of Arvo Part’s Spiegel im Spiegel and Morten Lauridsen’s O Magnum Mysterium, by the composer himself. I spoke to Meyers who had just moved to the Pacific Palisades with her husband and two daughters, aged four and six. She was off for an extraordinary roundtrip to Krakow, 15 hours each way, to play the Szymanowski Concerto and the world premiere of Jakub Ciupinski’s The Wreck of the Umbria, precisely scheduled so she would be back in time to take her older daughter to her first day of school.

—Laurence Vittes

Tell me about Einojuhani Rautavaara and Fantasia.

Fantasia means a lot to me. I had known Rautavaara’s music for a long time, since I was a kid who found his music browsing through the CD bins. It became a dream of mine that he would write something for me.

Was Rautavaara the ultimate composer you were after for a commission?

No. I’ve always gone after and harassed composers. I’m always thinking historically: Oistrakh, Auer, Joachim, Heifetz—they were muses for composers. They inspired such great music; just imagine if we had a concerto by Gershwin or Ravel or Rachmaninoff.

I would have just bugged the crap out of Rachmaninoff to write a violin concerto. Of course, plenty of composers say no and run the other way when they see me coming after them, but I’m tenacious.

How did the commission happen?

On a sudden impulse, out of the blue, I contacted Rautavaara’s publisher, Boosey & Hawkes, who put me in touch with him. I wrote and told him I was a big admirer of his. I asked if he would write something for me, he answered with a resounding yes, and sent me the music almost instantaneously, after which I flew to Helsinki to work with him.

What did you ask Rautavaara for?

He was 87 and I didn’t want to tire him out, so I asked for something shorter, a fantasy.

Can you describe Fantasia?

It is music like his Cantus Arcticus, with its electronic birdsongs, and his Angel of Light Symphony [Rautavaara’s Seventh Symphony, written in 1994 to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the founding of the Bloomington Symphony Orchestra]: ethereal and mystical. It is a soulful surge of emotion. I cry each time I play it. It was shocking when he passed; this was his last [composition for violin].

How closely did you work with him?

I arrived in Helsinki to find out he hand wrote everything, and it was hard to read. We made many, many changes, but mostly technical things like fingerings. And we changed many of the bowings to make the phrases sing as much as possible; he admitted he never had much confidence in his bowings, which he had in common with a few other composers. Otherwise, there was not one change, not one note, nothing, that I wanted to change.

What did Rautavaara say when he heard it for the first time?

He said, “I wrote such beautiful music.” And I thought, “You really did.”

When did you record the album?

We recorded the whole CD in May, broken up into two sections. We did the electronics part at the DiMenna Center for Classical Music in New York City, and everything with the Philharmonia in London. English orchestras are all quick studies, each with its own soul for music.

How did the new orchestration of Morten Lauridsen’s big choral hit come about?

I had been begging Morten for years to write something, really begging him, and he had been saying, “No, no, no, I’ve got a million commissions.” Then he heard me play Vivaldi’s Four Seasons in Pasadena, and he said, “I would love to do a special arrangement of this piece for you.” I said, “I’ll take one of those.” And the result is gorgeous.

You’ve made so many successful recordings. What’s your secret?

We laid down the CD in one and a half days of sessions, which were really packed. The secret on all recordings is having a great conductor to manage the time and musical pressures that come with recording, and a wonderful producer to make sure things flow. On Fantasia it was the amazing Wolf Ears Silas Brown and Susan Delgiorno; both were a complete joy.

How do recordings compare to live concerts?

Recordings may be more adventurous; it’s certainly a very different medium and process, but it’s almost impossible to compare. I love to perform live: There’s an electricity, a short fuse—a half hour and it’s over. With a recording, you’re working six hours at a stretch with one 15-minute break. You have to pace yourself, let go, and trust the engineer and producer to create the sound you’ve been working for.